Chapter 3 – Sniffing/monitoring the serial link between “Master PC” and “Target Device”

Communication between a hardware device and a PC via serial

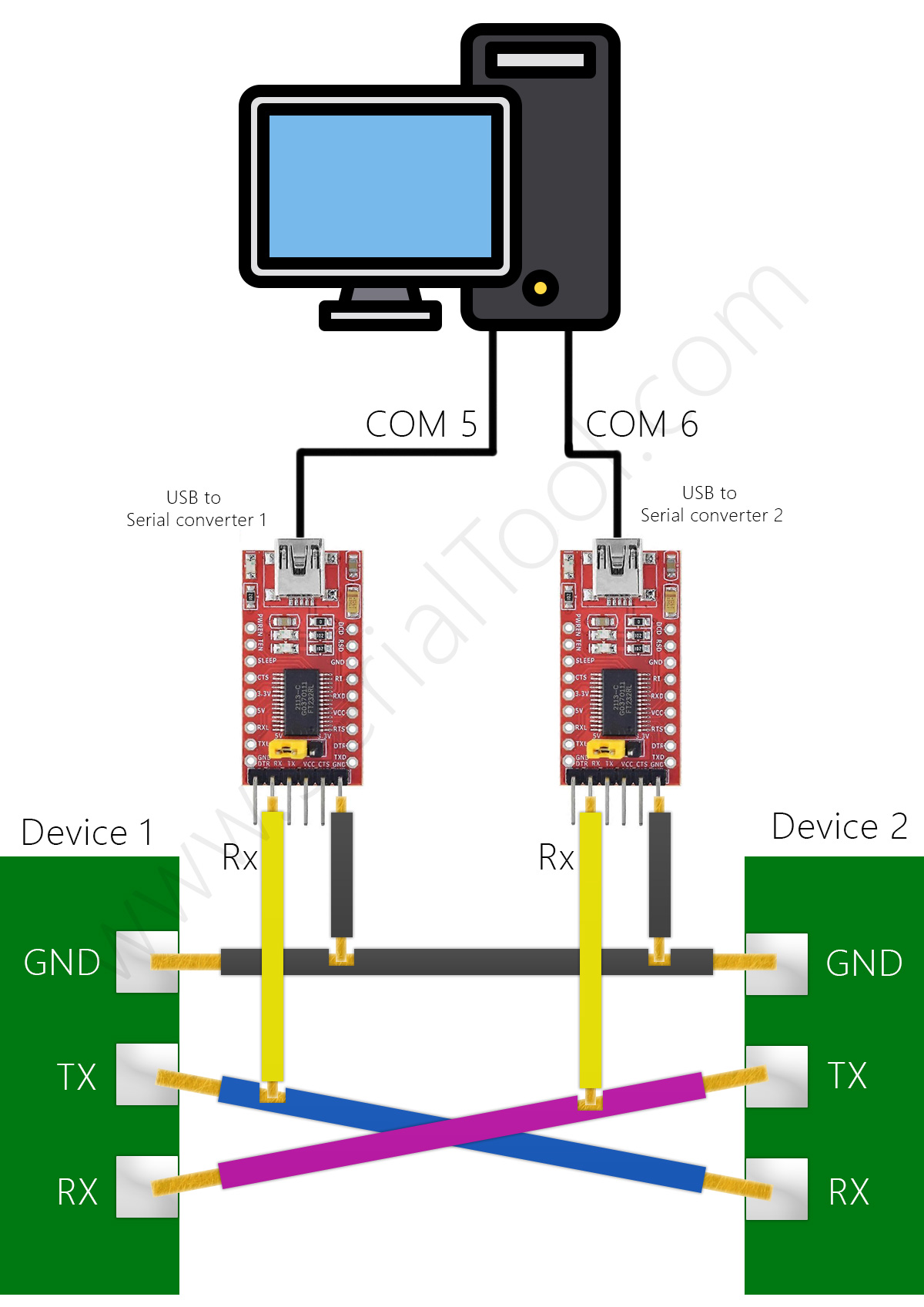

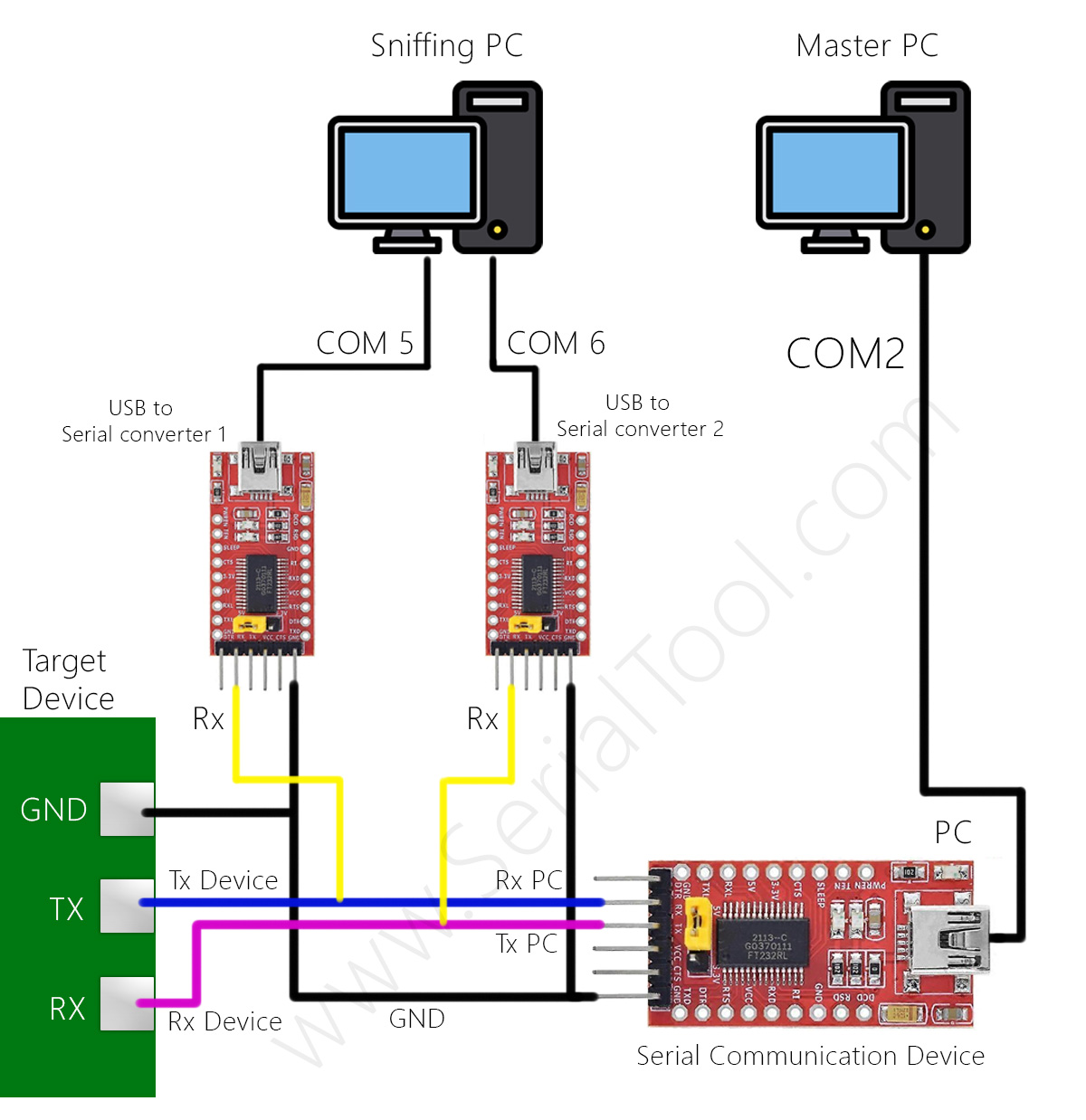

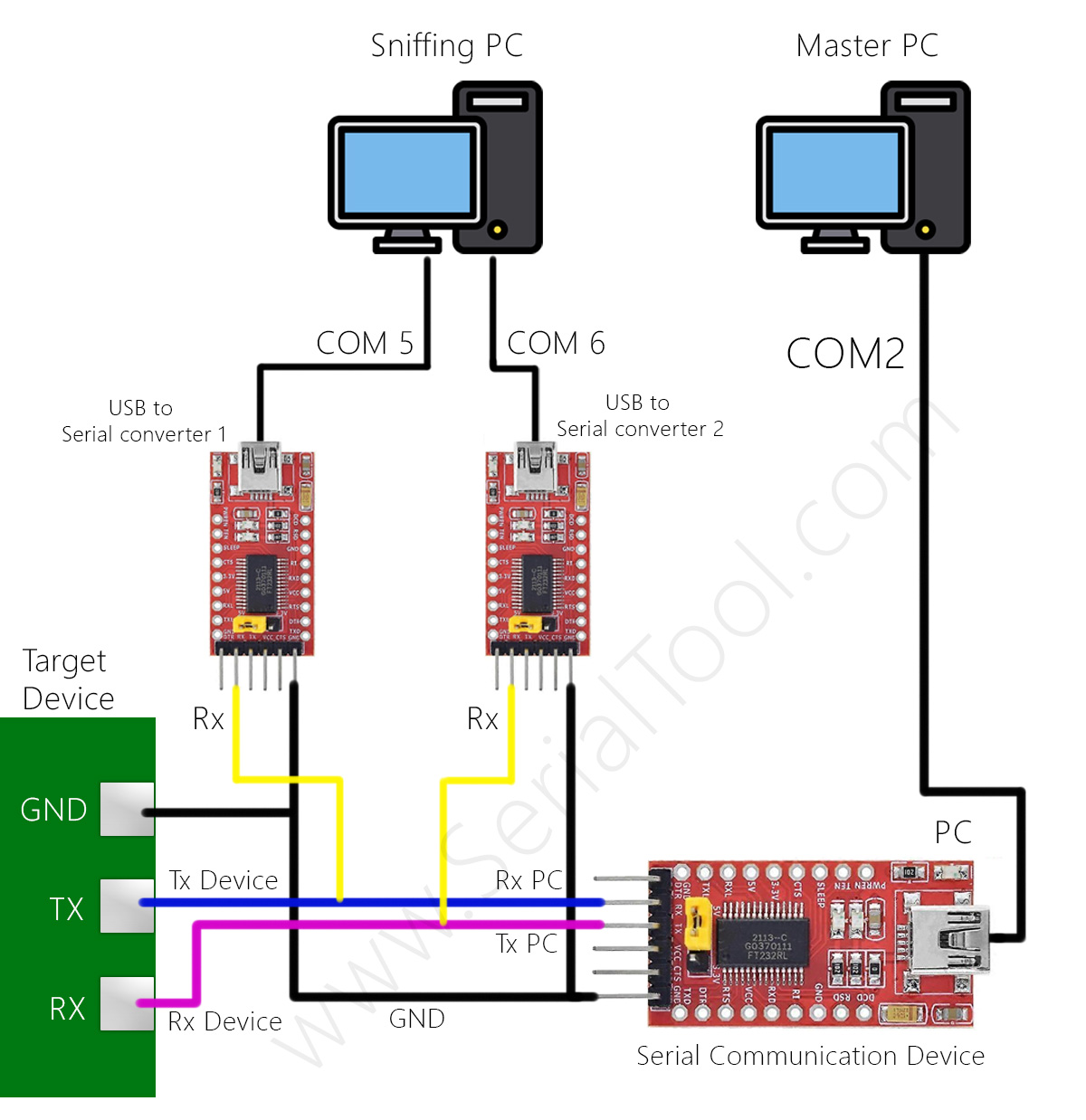

The Master PC (right) communicates with the Target Device through a

Serial Communication Device (typically a USB↔Serial converter:

UART/TTL, RS-232 or RS-485). The Sniffing PC (left)

opens two ports (COM5 and COM6) and, with two USB-to-serial adapters,

passively listens to the lines: on COM5 connect RX to the Device’s TX,

on COM6 connect RX to the PC’s TX. Grounds (GND) are common.

3.1 Purpose and concepts

We want to monitor and sniff the bytes traveling between software on the Master PC

and the Target Device, without interfering with the communication. It’s a typical passive physical man-in-the-middle:

two USB-to-serial adapters connected only in RX “read” each direction.

This is useful for debug, protocol analysis, and as a logger for auditing or reverse engineering.

3.2 Connections (step-by-step)

- COM5 (Sniffing PC) → connect the adapter’s RX to the Device’s TX (listen to what the Target sends).

- COM6 (Sniffing PC) → connect the adapter’s RX to the PC’s TX (listen to the Master PC’s commands).

- Common GND between the two adapters and the two devices (shared reference).

- Do not connect the Sniffing PC adapters’ TX: we remain listen-only (high impedance), without disturbing the line.

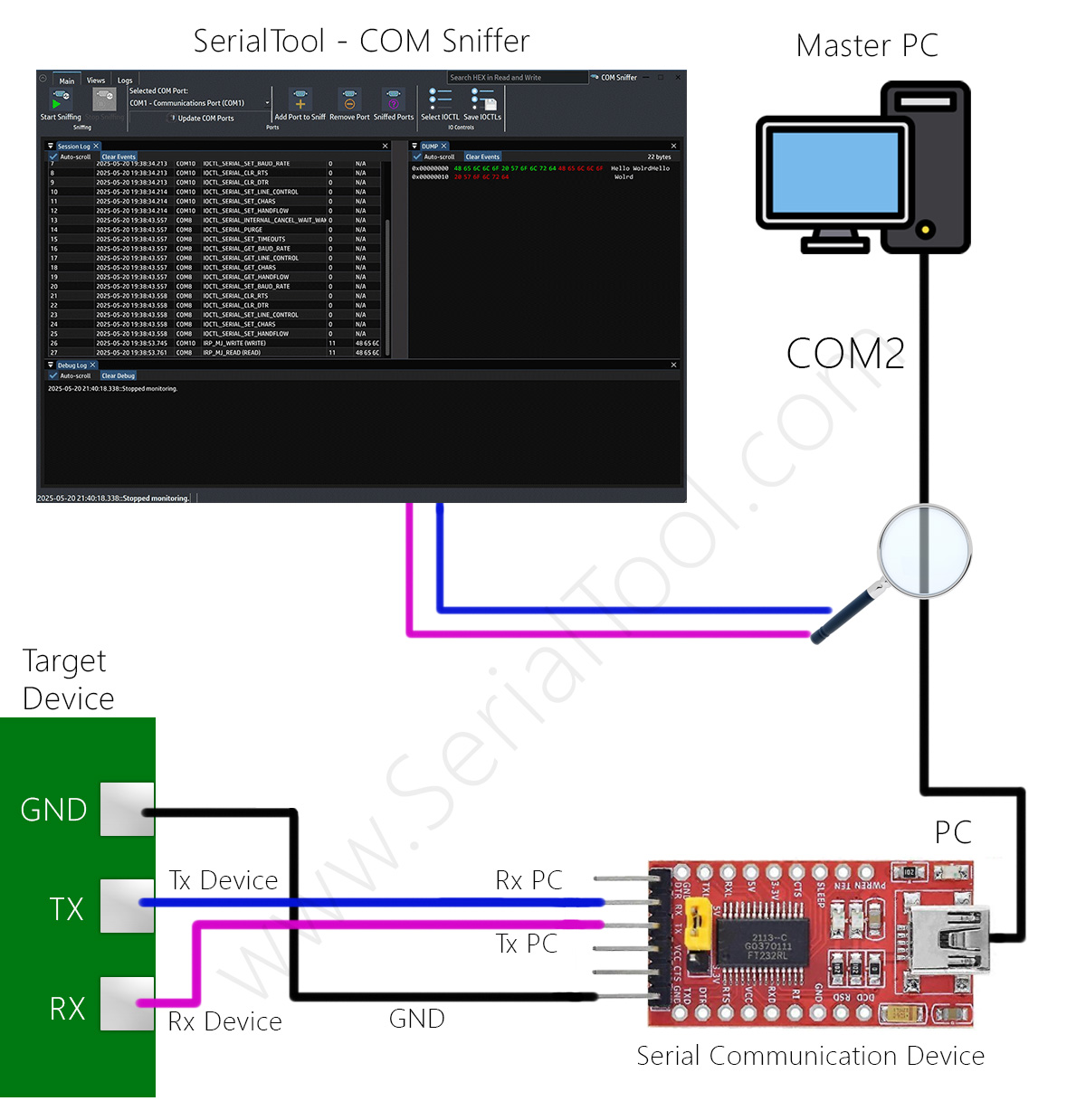

In SerialTool open two sessions: COM5 and COM6. In both, set

the baud rate and format identical to those used by the Master/Device (e.g., 115200-8N1). If you don’t know the baud,

try common values or measure bit duration with an oscilloscope/logic analyzer.

3.3 Same protocol, different levels: UART/TTL, RS-232, RS-485

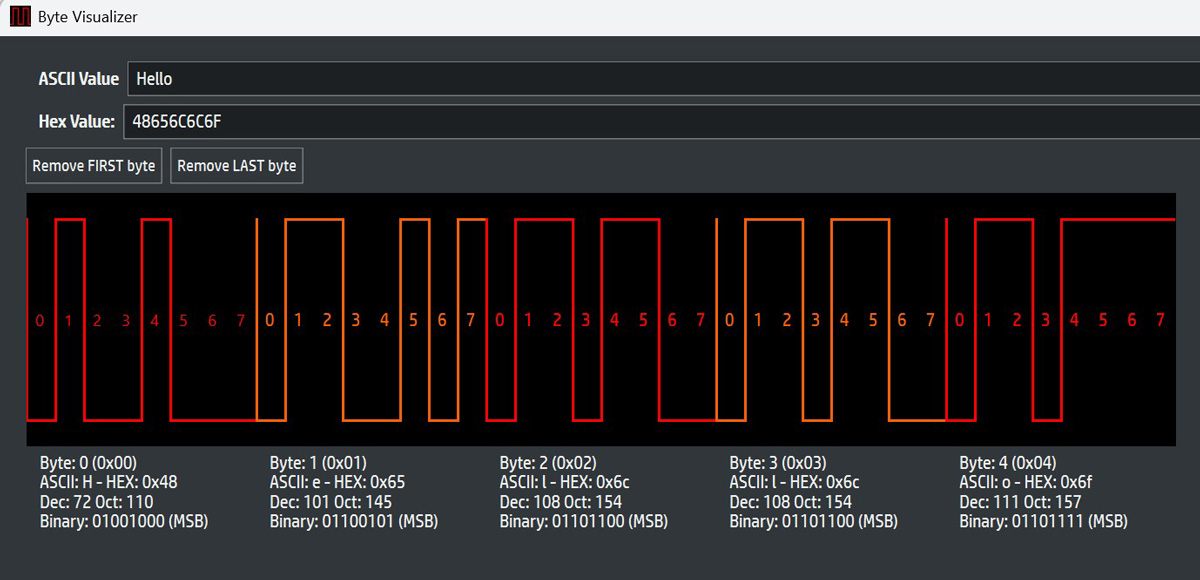

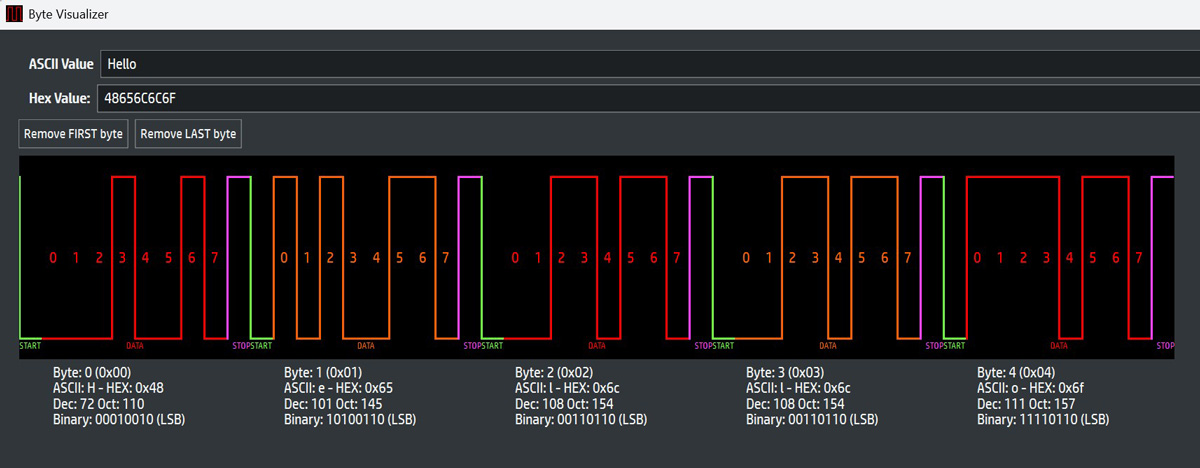

The asynchronous serial protocol (start, 7/8 data bits sent LSB-first, optional parity, 1+ stop) is the same.

Only the physical level the bits travel on changes:

- UART/TTL (3.3 V/5 V): single-ended signals, “1” high / “0” low.

- RS-232: inverted and ± voltage levels (typically ±3…±12 V), still single-ended.

- RS-485: differential on A/B pair, often half-duplex multi-drop; a common reference ground is recommended.

Therefore use the correct adapter:

USB↔TTL for UART, USB↔RS-232 for RS-232, USB↔RS-485 for RS-485. The frame remains identical, but electrical levels and topology (differential/termination) differ.

3.4 Where it’s used (CNC, industrial, etc.)

This setup is common in CNC, industrial machinery, PLC/HMI, robotics,

scales, POS, sensors, instruments, building automation, and in general any system where a PC/PLC

controls a device via serial. The sniffing method described here lets you monitor/sniff/debug/log traffic

for functional analysis, fault diagnosis, command tracing, and validation.

3.5 Modbus over serial

Serial ports often carry Modbus RTU/ASCII, a widely used master/slave (now client/server) protocol in industry.

The Master sends requests (read/write of coils and registers) and the Device replies.

SerialTool includes a Modbus client to quickly query registers (diagnostics and testing),

alongside the monitor/hex viewer useful to view raw frames (address, function, data, CRC).

3.6 Firmware update and parameterization

In the embedded world serial is widely used for firmware updates or passing parameters to the Target.

Examples: bootloaders on custom boards, ecosystems like Arduino, various microcontrollers. Here a developer may have two needs:

- Debug the application that talks to the Target (check commands, timing, errors).

- Reverse engineering an existing protocol (there’s a “closed” Master software talking to a board;

I sniff to understand its messages and then replicate them with my own software).

3.7 Practical notes and tools

- This setup typically requires two PCs (the Master and the Sniffing PC) and at least two USB-to-serial converters for bidirectional sniffing.

- For RS-232 use an RS-232 tap/converter; for RS-485 connect a receive-only interface to the A/B terminals

(respecting termination and polarity). On half-duplex RS-485 you’ll infer direction from timing context.

- We exclude control pins (RTS/CTS, DTR/DSR, DCD, RI); if the system uses hardware flow control, consider dedicated probes.

- In SerialTool you can enable HEX views, timestamps, and save as a logger (text/CSV/pcap) for later analysis.

In short: same serial protocol (asynchronous frames), different physical levels (TTL/RS-232/RS-485).

With passive two-RX tapping and software like SerialTool you can reliably monitor, sniff,

debug, and log communication between a Master PC and a Target Device.